A Neurotoxin Written into the Fossil Record

For most of human history, lead has been cast as the villain of modernity—a silent toxin woven into plumbing, paint, and petrol, spreading neurological harm in the wake of industrial progress. But recent research published in Science Advances1 turns that assumption on its head. It suggests that the entanglement between hominids and lead stretches back nearly two million years, deep into the evolutionary landscape that shaped the human brain.

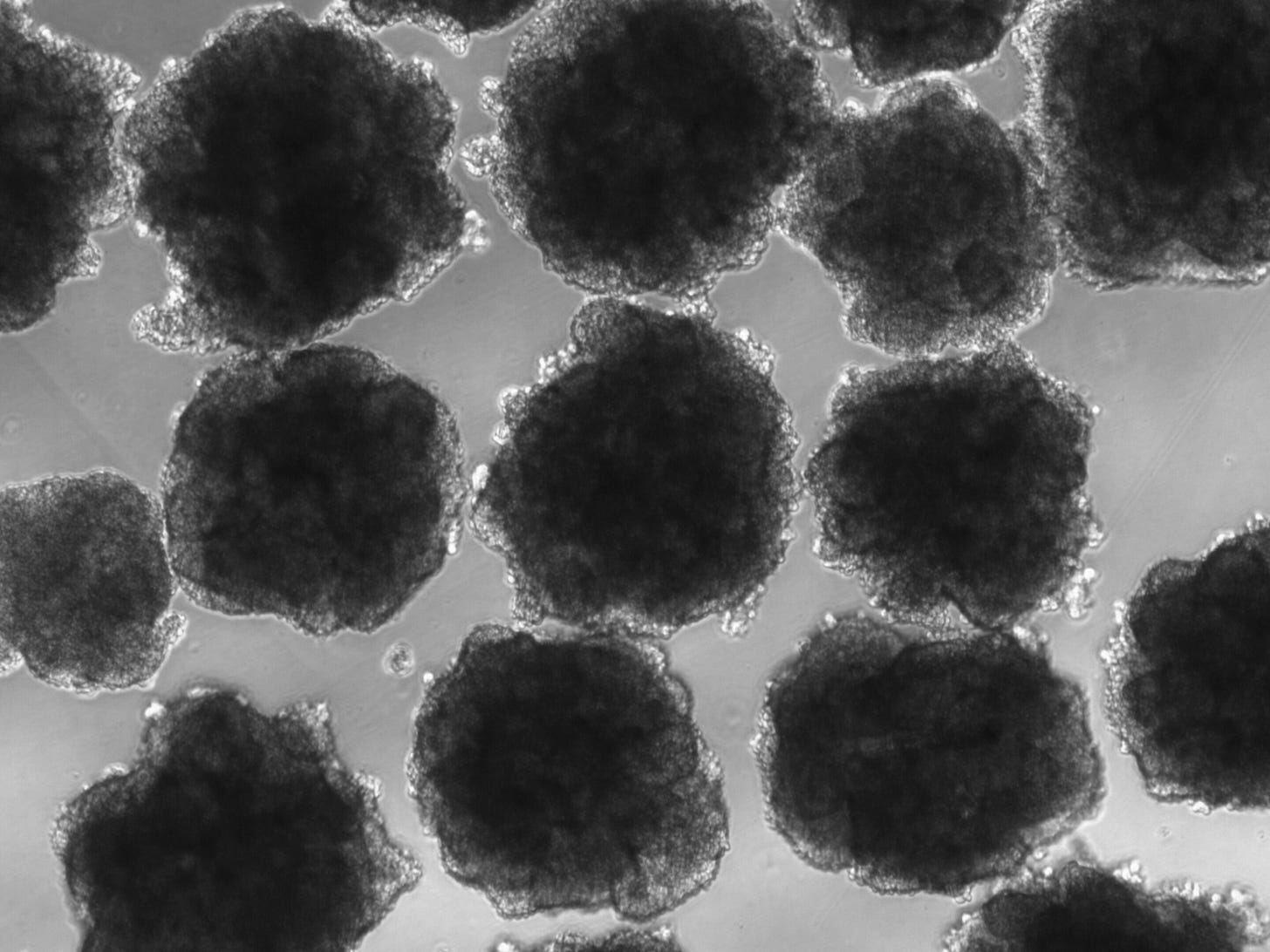

The study, led by Renaud Joannes-Boyau of Southern Cross University and Alysson Muotri of the University of California, San Diego, combines fossil geochemistry with experimental genetics. By examining lead isotopes in fossilized teeth and testing the effects of lead on lab-grown brain organoids carrying archaic genes, the team has reconstructed a forgotten ecological drama: ancient hominids repeatedly exposed to toxic metals in their environments—and possibly evolving in response to them.

In a sense, this is a story about adaptation to poison. Fossil teeth from Australopithecus africanus, Paranthropus robustus, early Homo, Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens all bear the same microscopic “lead bands”—chemical scars formed during childhood. These bands record episodic uptake of lead, sometimes from contaminated soil or volcanic ash, sometimes from groundwater running through metal-rich strata. To the researchers, these recurring exposures were not accidents of geography but recurring challenges that may have shaped how our nervous systems learned to cope with environmental stress.

“The finding that lead exposure was a persistent feature of hominid ecology reframes what we mean by environmental adaptation,” says Dr. Lina Petrovic, a biological anthropologist at the University of Vienna. “It suggests that our brains evolved in a world where toxicity itself was part of the selective landscape.”

Reading Childhood in the Teeth

To read this toxic history, the researchers turned to teeth—the most durable biological archive in the fossil record. As tooth enamel and dentin form during childhood, trace elements in the bloodstream are locked into their crystalline structure. Using high-resolution laser ablation at the Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group in Lismore, Australia, Joannes-Boyau and colleagues mapped the elemental composition of 51 fossil teeth spanning Africa, Asia, and Europe.

What emerged were distinct bands of lead alternating with normal growth layers, much like tree rings marked by periodic drought. Each band captured a window of exposure that could last weeks or months, suggesting that hominid children were intermittently ingesting lead through water, food, or dust.

The timing of these exposures often corresponded to seasonal stress periods—times when offspring were weaned or when food sources shifted. The researchers propose that physiological stress may have mobilized lead stored in bone tissue, releasing it back into circulation. In this sense, lead exposure was not just environmental but also internal, reactivated within the body’s own reservoir of toxic memory.

“Fossil teeth are diaries written in trace elements,” explains Dr. Mateo Rinaldi, a geochemist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “When those elements include lead, they become testimonies of both environmental hardship and biological resilience.”

Across species, the pattern was strikingly consistent. Australopithecus africanus specimens from South Africa showed cyclical exposures about two million years ago. Paranthropus robustus exhibited similar periodicity roughly 1.8 million years ago, and early Homo teeth from East Africa and Asia continued the trend. Even Neanderthals in Pleistocene Europe, separated by hundreds of thousands of years and thousands of kilometers, carried the same signature. Lead, it seems, shadowed hominid development wherever our ancestors lived.