Stretching between two great bends of the Nile, the Bayuda Desert in central Sudan rarely features in grand narratives of early human history. But a six-year archaeological project has placed it decisively on the map. Polish archaeologists have identified more than 1,200 new archaeological sites1 across this rugged expanse, pushing the timeline of human presence in this desert back nearly two million years.

Led by researchers from the University of Wrocław, the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw, and the Archaeological Museum of Gdańsk, the project not only confirmed Bayuda’s place in the prehistory of northeast Africa but also revealed the diversity of its use over millennia.

"This region, long overshadowed by more prominent Nile Valley sites, holds a stratified archive of human occupation and movement," said Prof. Henryk Paner, one of the project leaders.

The Salt Mountain and a Vanished Lake

At the heart of the desert lies Jebel El-Muwelha, known locally as the Salt Mountain. Nearby, archaeologists discovered traces of a paleolake that once held saline water, a rare find in an arid environment. This lake likely served as a source of natron, the mineral famously used in Egyptian mummification practices and early glass production.

Its location hints at the region’s wider economic and ritual significance. The team believes the natron resource may have connected this now-remote desert to broader ancient trade networks.

From the Oldowan to the Levallois: A Paleolithic Tapestry

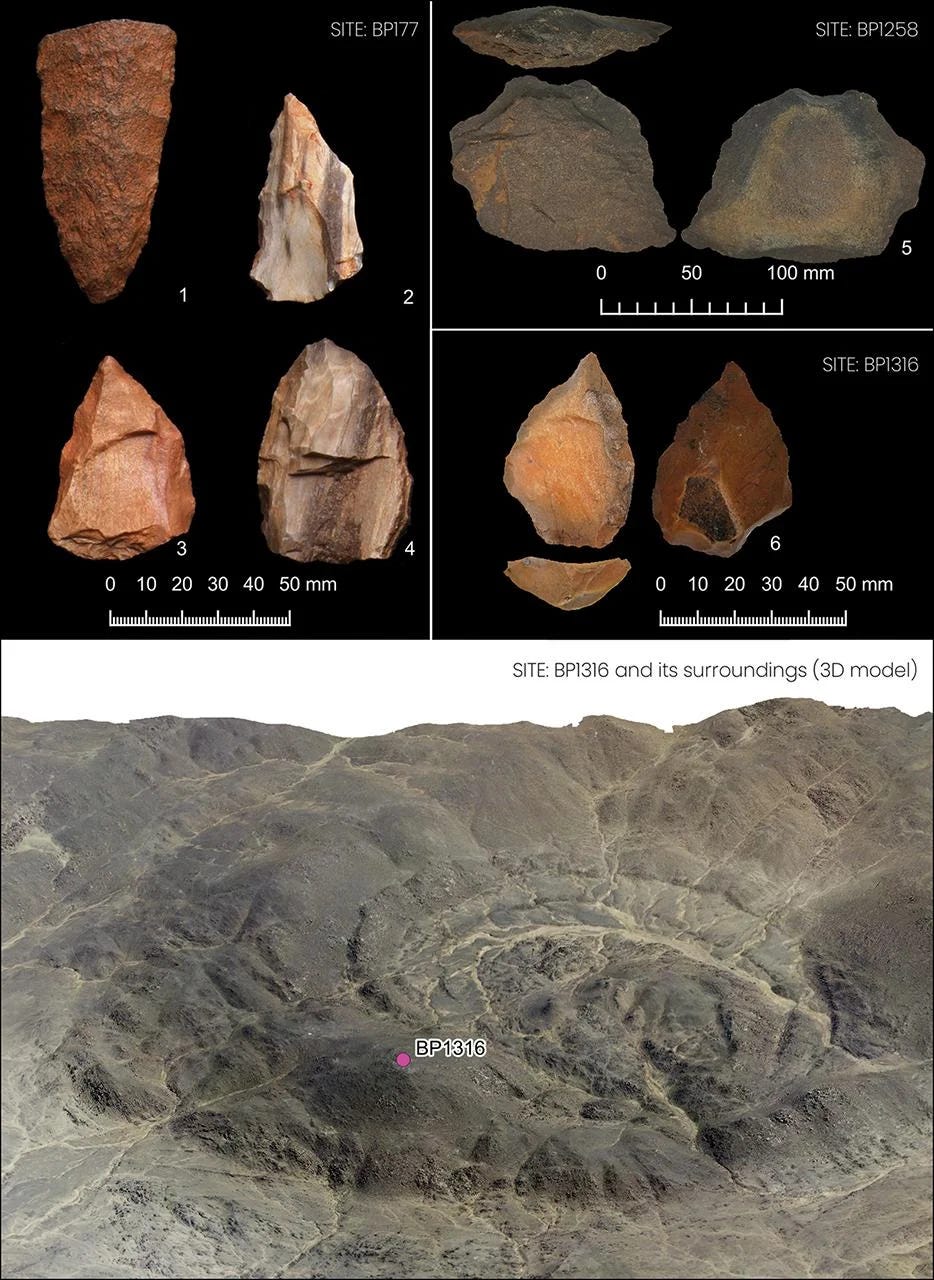

The earliest material recovered includes Oldowan tools, some of the oldest known stone technologies, dating from between 2.6 and 1.7 million years ago. Nearby, Acheulean artifacts such as hand axes and large bifacial flakes speak to the presence of early Homo erectus.

A later phase of occupation is marked by the presence of Levallois cores—a more refined stone-flaking technique associated with Homo sapiens. The method involves strategic preparation of a stone core to remove a single flake of predetermined size and shape.

"Its use involved the need to perform many intermediate steps to shape the core in a way that allowed the removal of a single flake of the intended shape," noted Prof. Paner. "This indicates the early presence of Homo sapiens in this part of Africa."

Cemeteries of the Living and the Dead

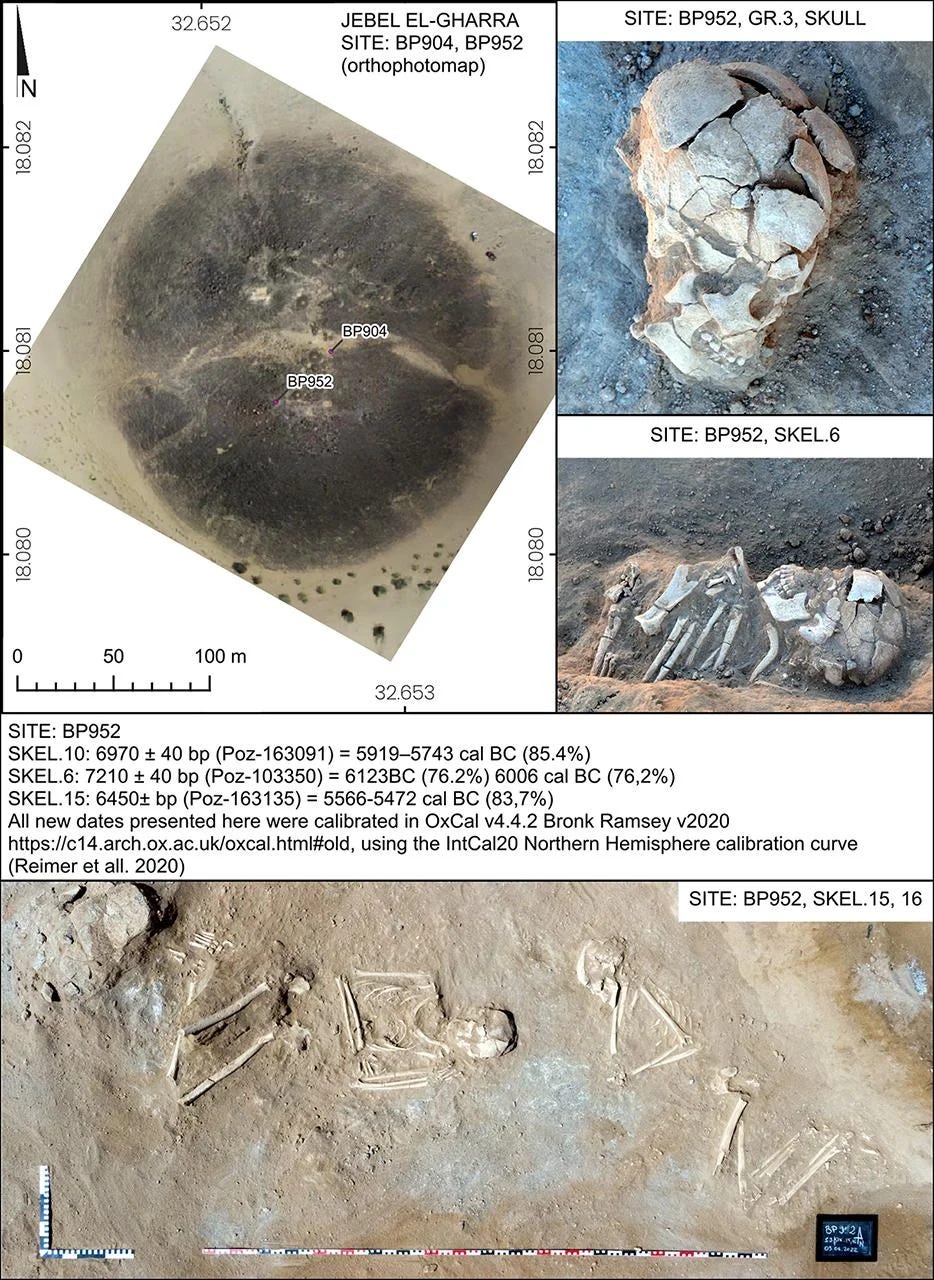

Beyond tools, the survey identified dozens of burial grounds. On the slopes of Jebel El Gharra, the team excavated what is now considered the only known Mesolithic cemetery in the Bayuda Desert. At least 16 adults were buried there in multiple layers, dating to the 7th to 6th millennia BCE. Shells, stone pendants, and ostrich eggshell beads accompanied the dead.

Even more intriguing were the beetle remains found inside a clay vessel at a Kerma culture cemetery (c. 2500–1500 BCE). These, along with faunal traces of savannah species, suggest that Bayuda was once greener—a landscape more hospitable to life and mobility.

Life on the Savannah Fringe

One particularly rich site, nicknamed the "Hunters' Settlement," was found at the base of Jebel El-Fuel. With nearly 3,400 stone tools, over 2,000 pottery fragments, and 300 animal bone remains, it provides a snapshot of a foraging community around 6000 BCE. The absence of domestic species points clearly to a hunter-gatherer economy.

"These tools and bones tell us that wild fauna were central to human subsistence," said archaeologist Małgorzata Osypińska, a faunal specialist on the project. "And their abundance suggests a semi-permanent or repeatedly visited settlement."

A Layered Landscape of Movement and Memory

The Polish team's work not only catalogues artifacts; it paints a portrait of the Bayuda as a palimpsest of human endeavor. From the oldest stone tools to medieval grave markers, the region records responses to environmental shifts, technological adaptation, and deep ritual life.

The discoveries also expand the known cultural boundaries of the ancient Kerma polity, hinting that its influence extended deeper into the desert than previously thought.

Bayuda's desert silence, it turns out, hides a story written in stone, clay, and bone—a record of people who made their lives at the edge of the Nile and the threshold of history.

Related Research

Hublin, J.-J., & Klein, R. G. (2013). The Origin of Modern Humans. Evolution of the Human Brain, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39979-4_13

Scerri, E. M. L., et al. (2018). Did our species evolve in subdivided populations across Africa, and why does it matter? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 33(8), 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005

Osypińska, M., & Osypiński, P. (2020). Hunter-gatherers on the Nile: The Early Holocene of the Middle Nile Valley. Quaternary International, 546, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.03.001

Paner, H., Masojć, M., Pudło, A., Michalec, G., Muntowski, P., Badura, M., & Osypińska, M. (2025). Prehistoric communities in the Bayuda Desert, Sudan. Antiquity, 99(403), e1. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.161