For centuries, the image of ancient Mesopotamian medicine has been split in two. On one side stand the pharmacological recipes, lists of plants, minerals, and animal products carefully recorded on clay tablets. On the other stands ritual, the murmured prayer, the incantation, the appeased god. Modern readers often assume these were parallel systems, sometimes overlapping, often competing.

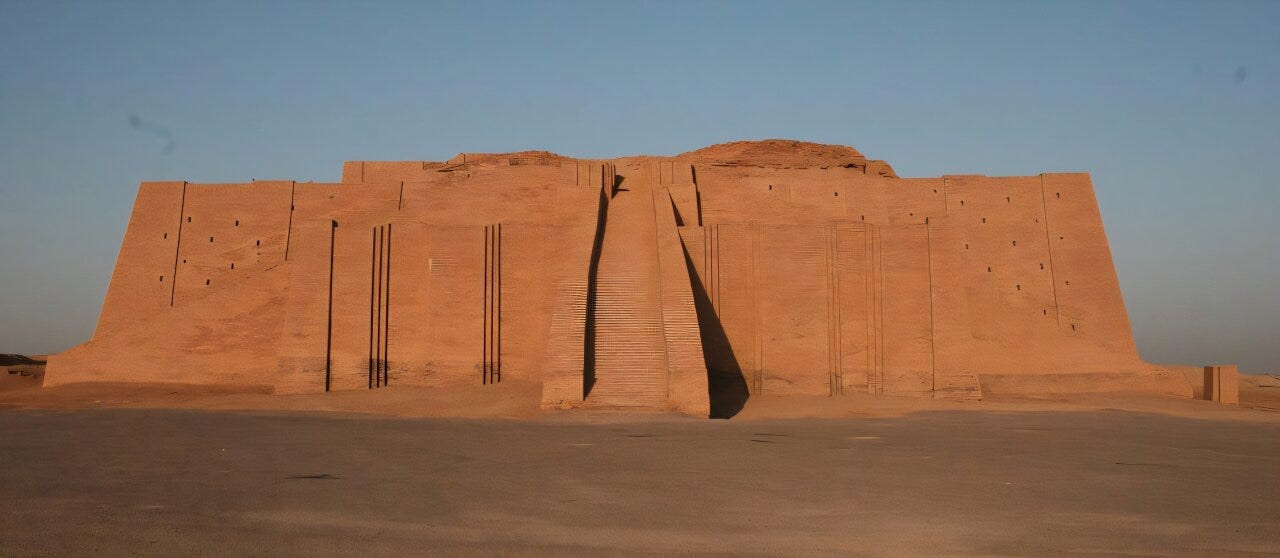

A close reading of a small and puzzling group of medical prescriptions suggests something subtler. In a handful of cases, healing required not only ointments and procedures but also movement. Patients were told to leave their homes and seek out a sanctuary. Recovery began with a journey.

Recent work1 by Assyriologist Troels Pank Arbøll reexamines these rare prescriptions and asks why certain ailments, and not others, demanded divine proximity. The answer does not reduce Mesopotamian medicine to superstition. Instead, it shows a system that treated the body, the environment, and the moral order as inseparable.