A Puzzle Too Big for Any One Discipline

For more than a century, scholars have tried to trace the lineage of human language back to a singular ancestral root. Some have pinned their hopes on a genetic mutation. Others have focused on the appearance of symbolic culture or the capacity for complex cooperation. But none of these ideas has ever fully explained how our species produces grammatical structures, learns endlessly varied vocabularies, and uses communication to build relationships as much as to transmit information.

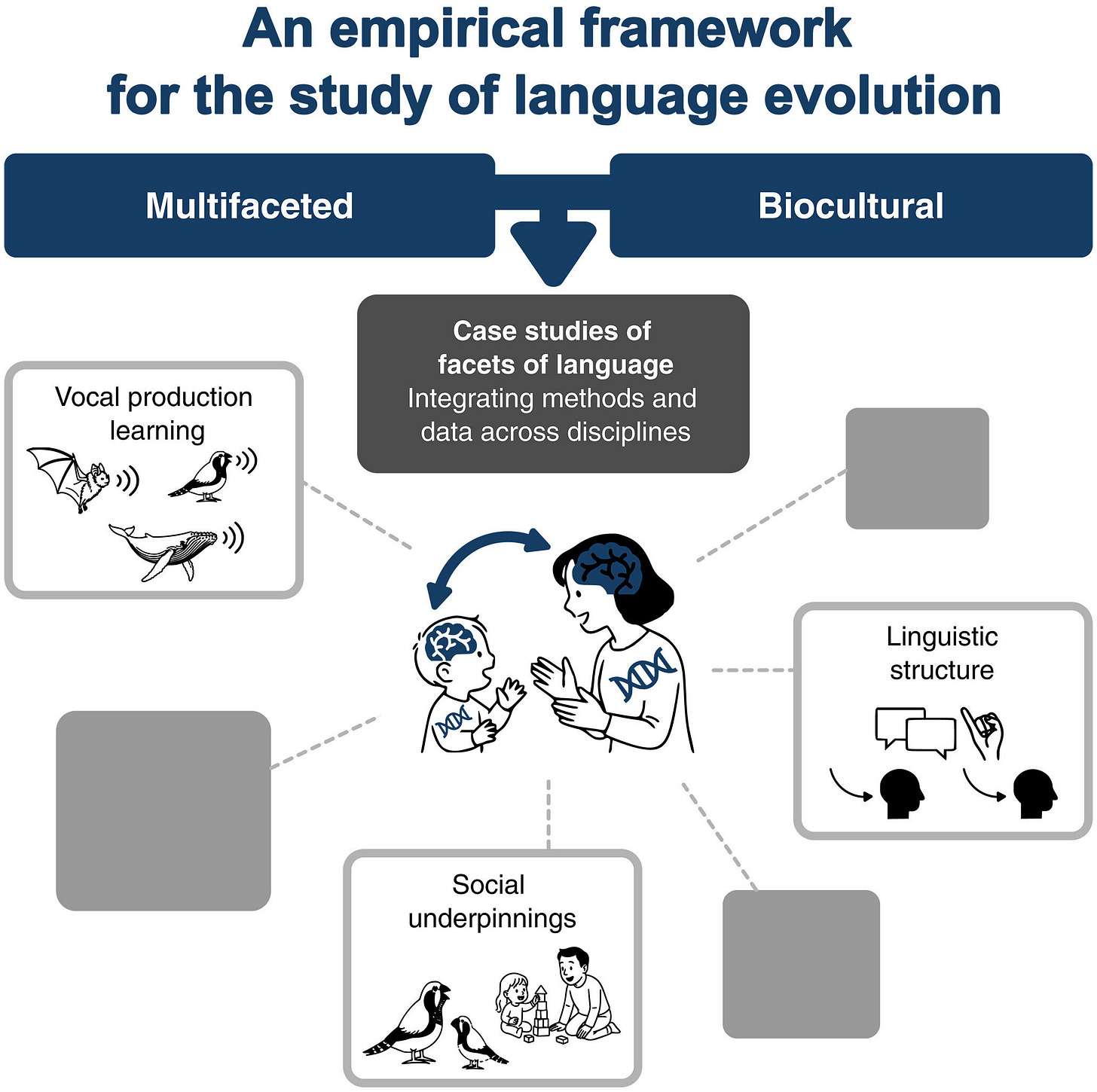

A new Science1 article, authored by an international team spanning biology, linguistics, anthropology, psychology, and neuroscience, argues that perhaps the search for a single origin has always been the wrong quest. Instead, they propose that language is best understood as the product of multiple evolutionary threads, knitted together through cultural transmission.

It is less a singular adaptation than a coming together of abilities. Vocal learning. Pattern recognition. Attention to social intention. A willingness to teach and, crucially, to be taught.

“Language depends on a constellation of capacities that rarely align in nonhuman species,” says Dr. Helena Draycott, a linguist at the University of Edinburgh. “Its roots must therefore be traced not to one trait, but to the meeting point of many.”

This is the heart of the new biocultural framework: human language emerges not from a lone biological invention but from the interaction of biological predispositions with the cultural systems that amplify and transmit them across generations.