The Ox and the Origins of Unequal Societies

Long before hedge funds, private property, or multinational tax havens, human societies were surprisingly equal. Across a wide range of Neolithic communities, archaeological evidence suggests that disparities in wealth—though present—were often kept in check. That balance, however, began to shift dramatically around 5,000 years ago. According to a new synthesis of archaeological, historical, and economic data published in the Journal of Economic Literature1, that change wasn’t just about economics. It was also political—and deeply cultural.

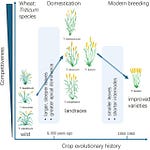

In the paper, economists Samuel Bowles of the Santa Fe Institute and Mattia Fochesato of Bocconi University argue that it wasn’t the invention of agriculture that sparked long-term inequality, but what came next: the ox-drawn plow. This innovation allowed a small subset of the population to control vast amounts of land—something that would have been physically impossible in a world where all farming was done by hand.

“Think of the ox and plow as a Neolithic robot,” said Bowles. “It displaced labor and enriched their owners.”

From Muscle to Material

The ox-drawn plow changed the basic equation of survival. Before its widespread adoption, farming success depended on human strength, cooperation, and proximity. In such contexts, physical labor could not be easily scaled, and communities often responded to growing disparities in wealth with what the authors call "aggressive egalitarianism"—social norms, or even violence, to reduce inequality.

But the plow shifted the playing field. Productivity was no longer limited by human labor but by how much land a family could command. Wealth became more easily accumulated, stored, and inherited—tied to property, not people.

“The key factor determining family income shifted from traits that were relatively equally distributed—strength and skill—to material possessions that could be passed on.”

Culture, Coercion, and the Proto-State

Technological change alone doesn’t guarantee inequality. In fact, Bowles and Fochesato argue, the enduring nature of wealth disparity required new political and cultural institutions to protect it. This period saw the rise of proto-states: centralized authorities that provided infrastructure and security—but also claimed the exclusive right to wield force.

By reducing the threat of local revolts or re-distributive violence, these early states stabilized inequality. At the same time, the cultural embrace of hierarchy and individualism began to replace long-held norms of communal sharing and economic leveling.

“The origin of enduring wealth inequality required both the change in technology and the state,” Bowles noted. “And a shift in cultural norms that made inequality seem acceptable—or inevitable.”

Echoes in the Age of Automation

The study’s relevance isn’t limited to the deep past. As artificial intelligence and other labor-replacing technologies emerge today, scholars are asking whether history might be repeating itself.

The comparison isn’t just metaphorical. Bowles and Fochesato point to AI as a modern analog to the ox-drawn plow. Both represent technologies that shift value away from labor and toward capital. Whether or not these shifts lead to renewed inequality, the authors argue, will depend less on the technology itself than on the surrounding political and social responses.

“Whether inequality increases again,” Bowles suggested, “is a political question—one that depends on who controls the new technologies and how societies choose to respond.”

Revisiting the Inequality Puzzle

What makes this study particularly compelling is its interdisciplinary reach. Drawing on decades of research, it integrates archaeological data on house size and burial wealth, textual analysis of early state formations, and economic models of inheritance and labor substitution.

Its conclusion is stark: The rise of persistent inequality wasn’t a natural outgrowth of farming—it was the outcome of a complex and contingent interplay between innovation, institutional development, and shifting cultural values.

Related Research

Scheidel, W. (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press.

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691165028/the-great-levelerBorgerhoff Mulder, M., Bowles, S., Hertz, T., et al. (2009). Intergenerational wealth transmission and the dynamics of inequality in small-scale societies. Science, 326(5953), 682–688.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1178336Bogaard, A., Fochesato, M., & Bowles, S. (2021). The plow, the horse, and the subjugation of women. Journal of Political Economy, 129(6), 1731–1775.

https://doi.org/10.1086/713096

Bowles, S., & Fochesato, M. (2024). The origins of enduring economic inequality. Journal of Economic Literature, 62(4), 1475–1537. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20241718