In a chilled lab somewhere in Europe or North America, a small piece of bone—perhaps a tooth or fragment of skull—lies inside a centrifuge tube. Within it are the genetic traces of someone who lived thousands of years ago. For a few hours, that bone becomes part of a vast, living experiment: one that promises to rewrite prehistory. But it also raises a question that science is only beginning to confront.

Who has the right to decide what happens to the DNA of the long dead?

Across continents, ancient DNA—or aDNA—research has transformed archaeology, revealing the genetic threads that connect early farmers, foragers, and travelers across time. Yet the same techniques that illuminate deep human ancestry are also challenging the ethics that have governed archaeology for decades. The issue has become especially urgent in Africa, where genetic diversity is greatest and where collaboration with descendant communities has not always kept pace with the speed of discovery.

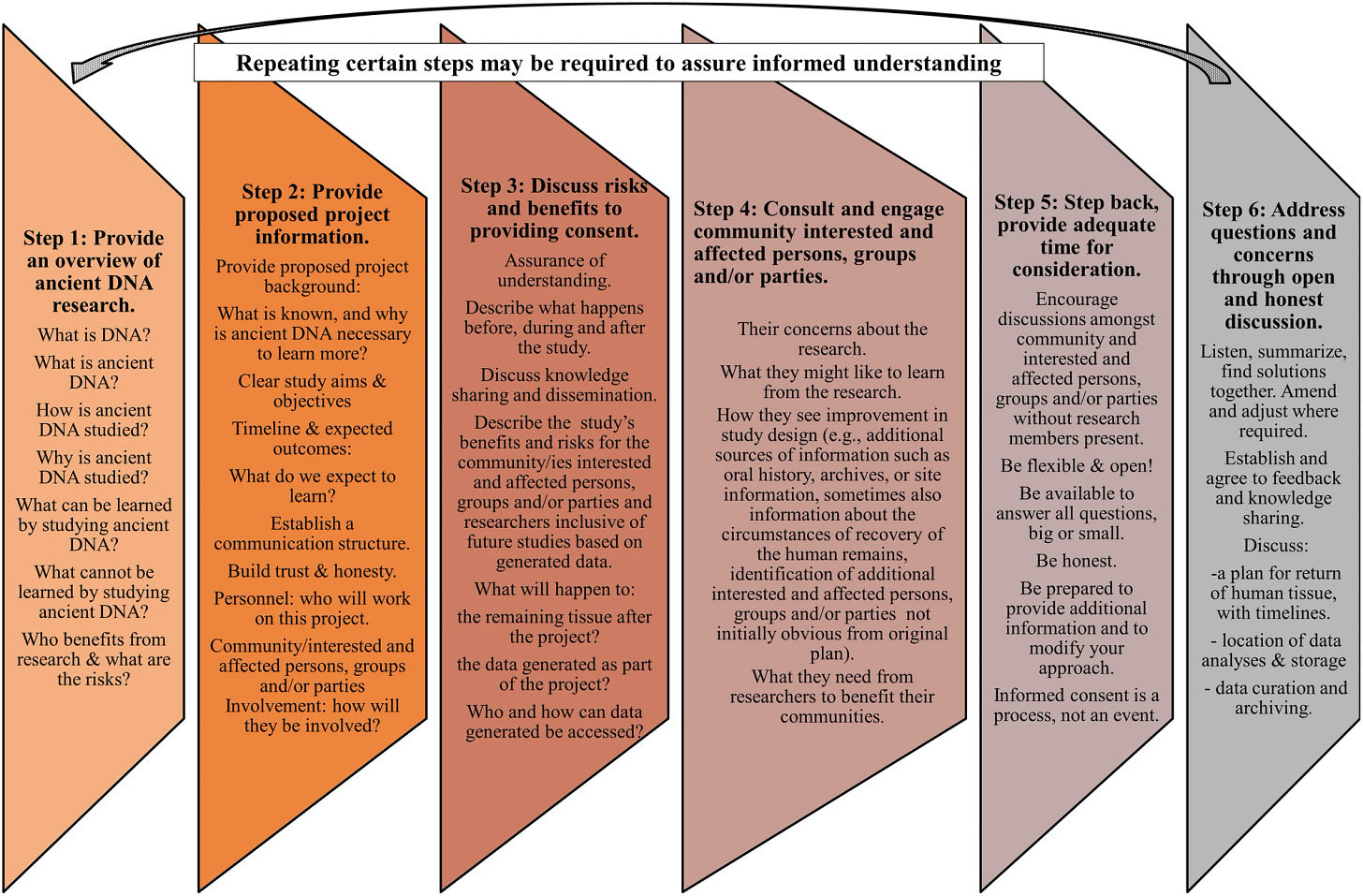

A recent paper in Communications Biology1 by Victoria Gibbon and colleagues at the University of Cape Town argues that consent in aDNA research must evolve just as rapidly as the science itself. Their proposal, called “informed proxy consent,” offers a framework that allows living communities to speak for their ancestors—an idea that could reshape how researchers handle human remains around the world.