Almost three decades ago, archaeologists uncovered a prehistoric mining complex in the Krumlov Forest of southern Czechia. The site’s shafts reached depths of eight meters, carved into the earth in search of chert, a fine-grained stone valued for blades, axes, and daggers. For years, the emphasis rested on the mining techniques themselves—until researchers encountered burials sealed within the shafts.

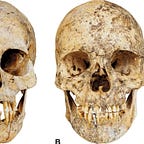

A new study published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences1 describes three individuals interred in one of these mining features: two adult women and a newborn. Their remains provide rare testimony to the lives of prehistoric miners and to the ritual landscapes surrounding resource extraction in the Neolithic and Eneolithic of Central Europe.

“Together with the Mauer burials in Vienna, the Krumlov Forest individuals are the oldest European mine graves known to date,” writes Eva Vaníčková and her colleagues.

Hard Lives Underground

The two adult women, designated H1/2002 and H2a/2002, were between 30 and 40 years old. Their skeletons bore the unmistakable traces of hard labor: vertebrae marked by osteophytes and Schmorl’s nodes, spines bent by hyperkyphosis, and muscle attachments enlarged from years of repetitive strain.

These signs point to lives spent working in forward-bent positions, consistent with mining in narrow shafts. One woman’s ulna showed evidence of a fracture that had never healed properly, suggesting she continued working despite injury.

Stable isotope analysis revealed another layer of detail. Both women were locals and consumed diets richer in animal protein than most Neolithic populations in the region. The researchers suggest that such a diet may have been deliberate—sustenance intended to maintain the physical endurance required for mining work.

Kinship and Separation

DNA analysis revealed that the two women were related, likely siblings. Both bore signs of stress during childhood, visible in Harris lines and enamel defects. Their shared trajectory of hardship seems to have continued into adulthood, ending in a shaft dug for stone rather than a grave prepared for ancestors.

The newborn, by contrast, was not biologically related. Genetic testing showed no direct kinship to the two women. The child had died at full term but for reasons unknown was buried alongside the miners. The placement invites speculation: Was the newborn part of a ritual dedication? Or was the interment symbolic, tying fertility, death, and the subterranean world together in one act?

Stone, Symbol, and Sacrifice

Chert was not a rare resource. In fact, it could often be collected from the surface. Its value, then, may have been less about practicality than symbolism. Chert blades and axes appear in ritual deposits across Neolithic Europe, often linked with prestige and ancestral meaning.

As Vaníčková and colleagues note:

“The practical value of the mined chert was minimal, as it could be collected on the surface. However, it is questionable whether people associated the stone from the depths of the earth with some ancestral legacy, meaning that its value was subjective.”

If chert was seen as a material bound to the underworld or ancestral powers, then miners themselves may have been drawn into that cosmology. The burial of the two women in the shaft may not have been accidental or pragmatic. It may have been a symbolic act—returning the miners, and their labor, to the earth.

Gender and Power in the Eneolithic

Why women? The evidence suggests these individuals did not choose their path. The unhealed fracture hints at coercion. Some scholars propose that as male roles expanded in Eneolithic societies, women may have been forced into arduous labor such as mining. Strength was no longer the main criterion; vulnerability to compulsion may have been.

This interpretation positions the Krumlov Forest burials within broader debates about gender, labor, and inequality in prehistoric Europe. Were women exploited as expendable labor in the mines? Or were they ritual specialists whose work carried symbolic importance? The burial of a newborn alongside them only deepens the enigma.

Questions Still Buried

The Krumlov Forest shaft preserves more than bones and stones. It holds questions that cut to the core of prehistoric life: Who mined the earth’s resources, and under what conditions? How did societies assign meaning to the extraction of stone? And how were miners themselves integrated—or sacrificed—into those beliefs?

As more multidisciplinary analyses are applied to such burials, the silent record of labor, kinship, and ritual carved into bones and isotopes will continue to speak.

Related Research

Knutsson, H., Knutsson, K., Apel, J., & Glørstad, H. (2018). “Technology of the Sacred: Neolithic Axes and the Materialization of Cosmology in Scandinavia.” Antiquity, 92(364), 1439–1455. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.148

Sørensen, M. L. S. (2013). Gender Archaeology. Polity Press.

Turek, J. (2015). “Ritualized Practices in the Neolithic Mining of Central Europe.” Documenta Praehistorica, 42, 255–267. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.42.17

Borić, D. (2007). “Body Metaphors and Technologies of Transformation in the Neolithic of the Balkans.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 17(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774307000412

Vaníčková, E., Vymazalová, K., Vargová, L., Tvrdý, Z., Oliva, M., Brzobohatá, K., Fialová, D., Skoupý, R., Krzyžánek, V., Fišáková, M. N., & Drozdová, E. (2025). Ritual burials in a prehistoric mining shaft in the Krumlov Forest (Czechia). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 17(7). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02251-1